Australia doesn’t want bikie boss Raymond Elise. He’s happy to leave but is stuck in a crowded detention centre threatened by Covid-19 with no idea when he and his family can fly home to New Zealand.

In the middle of Covid-19 lockdown in Melbourne, Raymond Elise was loading groceries into his car outside a supermarket when armed police jumped from a van and forced him to the ground at gunpoint.

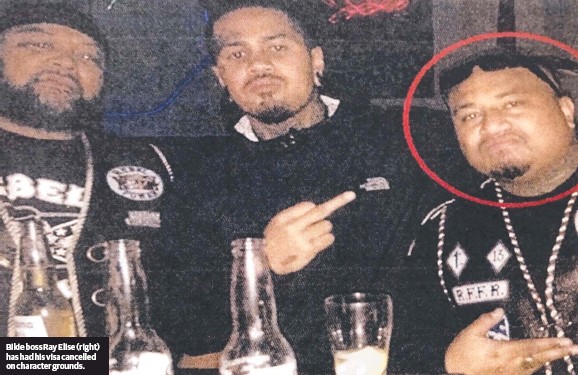

With members of the anti-gang Echo Taskforce standing over him, Elise, the Victorian president of the Rebels motorcycle club, was told his visa had been cancelled and he was an unlawful citizen in Australia, the country he’d called home for nearly a decade.

In the days after the April 24 car park encounter, Australian Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton said the 32-year-old, who police believed was an “influential organised crime figure”, would be deported.

“I have cancelled the visa of a senior member of the Rebels in Victoria because the Rebels is a notorious group of thugs, drug dealers and thieves,” Dutton told local media.

A month later, Elise, who grew up in Mangere, Auckland, is being held in a Melbourne Immigration Transit Accommodation waiting to be deported to New Zealand.

Like dozens of other Kiwis sitting in detention centres across the Tasman, his future is uncertain.

Covid-19 halted deportations between Australia and New Zealand in mid-March and it’s unclear when they will resume.

“I’m happy to go back [to New Zealand]. The problem is, we don’t know how long we’ll be here or when we’re able to return. It might be a month, it might be 12 months. It’s all in limbo at present,” Elise told Stuff.

“If they know that there’s a delay in deporting detainees back to New Zealand why are they still detaining them and bringing them into these centres? These centres are getting full.

“How do I get out of here?”

More than 2000 people have been deported to New Zealand since Australia began hardline enforcement of a populist immigration policy in 2014.

The deportees are known as 501s, named after the section of the Migration Act that allows the cancellation of their visa.

Most have criminal records, but others, like Elise, are deemed to be of bad character because of their association with bikie clubs and “apparent ties to organised crime”.

In February, Community Law and the NZ Human Rights Commission launched a campaign to put pressure on the Australian Government to address its “unfair and inhumane” immigration policy.

Police figures show 2074 people have been deported from Australia to New Zealand since January 1, 2015.

Community Law’s chief executive Sue Moroney said it was “inexplicable” Australian authorities were adding people to already crowded detention centres while deportations were on hold.

“There has been huge tension in these centres because of the fear of contracting Covid-19 in a confined environment.”

“I know they feel like sitting ducks. If Covid-19 was to enter their compound it would rip through the place like wildfire. It’s a very volatile situation they are adding people to.”

Inmates have written to Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison asking to be detained in the community, with family, but their pleas haven’t been acknowledged.

Sue Moroney, chief executive of Community Law Centres.

Elise, a father of four children aged 6 to 13, told Stuff he was frustrated he wasn’t allowed to fly home immediately and isolate like other New Zealand citizens.

The bikie said he’d heard deportations were on hold because Australian Border Force staff who accompanied detainees across the Tasman would have to isolate upon their return.

Had he been given the chance, he would have left Australia voluntarily with no escort as he wasn’t a threat to anybody.

Elise said he and his partner moved to Australia in about 2010 in search of a better life.

In New Zealand he’d amassed convictions for assault, threatening behaviour, possession of an imitation firearm and unlawfully presenting a firearm at a person.

None of those crimes, some of which he committed as a youth, resulted in a jail term.

Since arriving in Australia, Elise said he’d lived a crime-free life and worked hard, most recently in the construction industry as a labourer, to support his family.

He became involved with the Rebels about seven years ago through friends and quickly worked his way up the ranks by being a “committed member”.

“I did the ks on the bike.”

In April 2018, Elise, who also uses the names Ray Siloi and Mace Raymond Sitoper, became the Victorian state president of the club, overseeing seven chapters and about 130 members.

Australian media reported last month that police gave a report to the Department of Home Affairs in February, detailing concerns about his growing “influence on organised crime” in Melbourne.

Among the reasons given for the cancellation of Elise’s visa were his criminal offending from a young age, disregard for Australian laws and “extensive network of criminal associates”.

“Bikies are the biggest distributors of amphetamine in the country and are all round bad people,” Dutton said.

“Outlaw motorcycle gangs destroy lives, families and communities and I will do everything in my power to protect Australians from criminals who seek to do us harm.”

Elise said he was not involved in organised crime.

“Where’s the proof?”

“I haven’t been convicted of no crime in Australia and I’ve been here close to 10 years. I’m not proud of my past history in New Zealand… but who doesn’t make mistakes when they are young.”

“There’s good and bad in all walks of life – you can’t paint everyone with the same brush. They say senior members have knowledge of what happens. We don’t have knowledge of nothing. We don’t know what every member does in their own time. I feel like they’re punishing me for something I’ve never done.”

However, fighting the cancellation of his visa wasn’t an option, he said.

Dutton had too much power and the system was unfair.

“It’s not worth challenging because it goes back to the same man that cancelled my visa and he has the last say. I can’t be sitting in here for a year or two fighting something that I can’t win. I’ve chosen to go back [to New Zealand] because I’ve got a young family.”

Elise said he was the sole-breadwinner for his family, whom he had not seen since he was detained due to Covid-19 restrictions.

They’d packed up their belongings and were “doing it tough” while waiting to learn when he would be removed from Australia.

He said he had lined up a job in the Auckland construction industry.

The Rebels, Australia’s largest motorcycle club, expanded into New Zealand in 2011 and established chapters across the country.

Asked whether he would link up with a Kiwi chapter of the club, Elise said: “I’ll sort that out when I get there. I love riding.”

Australia’s Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton has spearheaded the deportation of people to New Zealand.

The arrival of the 501s has radically changed New Zealand’s underworld.

New clubs, most notably the Comanchero and Mongols, have become established and membership increased nearly 50 per cent in the four years to June last year.

Documents obtained under the Official Information Act show the national gang register carried the names of 82 of the 501s on May 16.

Police previously said many of the deported club members were powerful and influential figures in the Australian underworld, who brought with them professionalism, a new flash image and significant international connections.

The arrival of the new international clubs – known for their propensity for violence, particularly their use of guns – has led to clashes as rivals try to protect their turf.On March 31, there were 1373 people in immigration detention in Australia, including 159 New Zealanders.

Elise’s case shows those numbers have increased since then.

The Rebels expanded into New Zealand in 2011.

Authorities in New Zealand are planning for a wave of deportations, but none were able to say when they were likely to resume.

Those involved in helping the deportees settle in New Zealand, like Prisoners Aid and Rehabilitation Society (PARS), are concerned about where they’ll be housed.

“Having so many people arrive at once is going to be really difficult,” said Aimee Reardon, the manager of the Christchurch branch of PARS.

Trans-Tasman relations have frayed over the deportations with Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern publicly blasting Morrison at a joint press conference in February.

In a statement, Foreign Minister Winston Peters said the Government had not requested community detention for detainees in Australia.

New Zealand officials continued to “discuss Australia’s deportation and immigration detention policy with the Australian Government, including with regard to the impact of Covid-19”, Peters said.

“We have been advised that the Australian Border Force and its service providers have put in place every measure possible to prevent the possibility of Covid-19 entering and spreading in immigration detention facilities across Australia.”

In a statement, an Australian Border Force spokesperson said availability of flights and travel restrictions due to Covid-19 had impacted deportations.

The department was working with New Zealand officials to “ensure that New Zealand citizens currently in detention who want to return can do so as soon as possible”, the spokesperson said.

Deportees needed to be escorted to New Zealand “based on a number of risk factors including safety of the individual and the public”, they said.

Dutton did not respond to requests for comment

Make sure you have subscribed to our Facebook page or Twitter to stay tuned!

Source: Stuff