ALBANY — For more than a decade, Joseph Brady was a go-to guy in the state Legislature for the leaders and lobbyists associated with New York’s public sector labor unions.

In his role as the longtime legislative director for state Assemblyman Peter J. Abbate Jr., Brady was the gatekeeper for the 71-year-old Brooklyn Democrat — a state lawmaker since 1986 whose leadership of the chamber’s Governmental Employees Committee gave him significant influence over labor issues.

For anyone seeking support in the Assembly on a matter involving labor, their first stop was often Abbate’s office — and that contact usually would begin with a conversation with Brady, who had previously been a legislative representative for former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

But what Brady’s colleagues at the Capitol were apparently unaware of is that his dress shirts and ties concealed the tattoos that provided clues to the hulking 40-year-old’s double life as a co-founder of a notorious chapter of the biker club East Coast Syndicate. The Capital Region motorcycle club formed about six years ago and has since attracted the attention of law enforcement for its members’ alleged affinity for drug use and violence. The group is also the focus of a homicide investigation in Saratoga County.

Yet Brady’s ability to separate these divergent personalities — affable legislative aide, leader of a small but infamous biker club — collapsed last weekend when he was arrested on charges of sexually abusing an incapacitated 18-year-old woman at his Watervliet apartment.

A few months before his unexpected arrest, the Times Union had begun examining the mysterious life of the $108,000-a-year legislative aide who in early 2016 had inexplicably filed paperwork with the New York Department of State to obtain non-profit status for his motorcycle club, whose members wear patches with the moniker Syndicate 518, an apparent reference to the region’s area code.

‘A certain presence’

Just as there are strict rules governing the operations of the state Assembly, the East Coast Syndicate club that Brady and three others co-founded has its own guidelines. They adhere to an eight-page “constitution” that dictates everything from who can hang out with them to how they handle instances of a member sleeping with another member’s “ol’ lady” — which could result in “an ass kicking and kick-out from the club,” according to a copy of the club’s bylaws obtained by the Times Union.

The rules spell out the roles of board members, president, vice president and secretary, and also detail the duties of enforcer, captain and sergeant at arms, who is tasked with defending members from “outside threats.”

The bylaws require attendance of all members at meetings — wearing their colors — and forbids them from fighting one another with weapons. That latter rule conflicts with another section titled “Respect,” which notes that no fighting among members is allowed and “any punches to be thrown will be done by the Captain.” The club collects dues from its members — $50 a month and an annual $200 payment — although Brady and his three co-founders are exempted from paying those fees.

Their members also are required to attend club meetings or face a $25 fine, “except for guys in hospital or jail,” the bylaws state. Anyone who gets thrown out of the club or quits faces “probably an ass kicking.”

“We are a independent organization building a family of brothers!” one of the founders wrote in a Facebook post earlier this month. “We live by our own standards, our own rules, our own structure. Respect is earned, and a equal level of respect is returned!! That is a code of our lifestyle and our structure!”

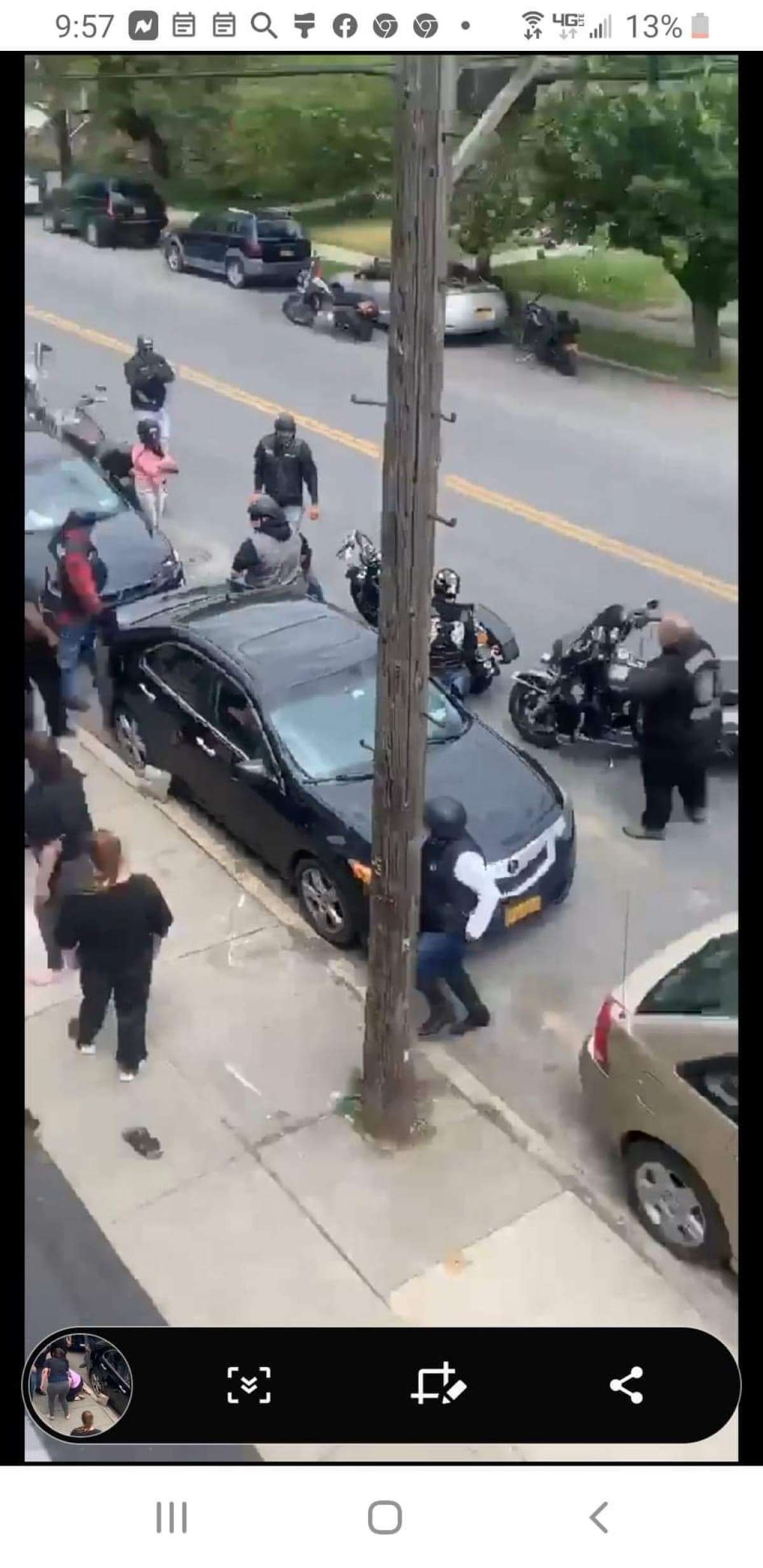

In another post, from August, Brady stood at the end of a group photo with four rows of more than 50 men, all wearing East Coast Syndicate colors. It’s unclear how many of those pictured were members of his chapter. In other undated photos provided to the Times Union, Brady was visible standing on a Troy street, his arms crossed and motorcycles parked across the roadway, as members of his outfit allegedly beat a disrespectful teenager during a melee in broad daylight.

Abbate, who declined to be interviewed for this story, announced on Monday that he had fired Brady a day earlier, after the Times Union first reported his arrest and connection to the assemblyman.

Many who dealt with Brady — and have high praise for Abbate’s attention to labor issues — expressed shock at learning the longtime aide had hidden such a dark secret.

“He was in a pivotal role,” the head of a law enforcement union, speaking on condition of anonymity, said of his dealings with Brady at the state Capitol. “He was actually an affable guy. Level. Not a loud guy by any measure. But he had a certain presence, if you will. He was just a good guy that you could talk to, and he would get it.”

Thomas H. Mungeer, president of the New York State Troopers Police Benevolent Association, had a similar view of Brady.

“I’ve known him for over a decade,” Mungeer said. “Any dealings I had with him professionally, I had no problems with him at all. In that respect he was a good guy. I will say this about him: When you did deal with him, he was just a regular guy. … You could talk to him, you had a relationship — he was not a politician wannabe.”

Teeth

The public unraveling of Brady’s two worlds took place after he was arrested Saturday by Watervliet police and charged with sexually abusing an 18-year-old woman after allegedly plying her and her 16-year-old boyfriend with methamphetamine and alcohol during a weekend binge.

The parents of the boy, who was already battling substance abuse problems, had apparently left him at Brady’s Third Avenue apartment for safe harbor as they sought out a drug rehabilitation facility for their son to get treatment, according to sources briefed on the investigation.

But the arrest was not Brady’s first brush with law enforcement.

Brady and other members of his club have been a focus of an investigation into the disappearance of a Saratoga County biker, Michael P. Ahern of Stillwater, who was last seen on Jan. 6, 2019, nine days before he was reported missing. His pets and vehicles were still at a garage on Brickyard Road where Ahern, who would now be 44, had resided.

The building, which Ahern rented, had served as the clubhouse for his own now-defunct motorcycle club, Rolling Pride. Police believe Ahern may have been killed there and his body disposed of elsewhere, according to a person briefed on the case, because cellphone records indicated he had been at that location around the time he vanished.

State Police forensic investigators, in coordination with Saratoga County sheriff’s deputies and local police, scoured the Brickyard Road property last year for evidence of what happened to Ahern, who had dealings with members of the East Coast Syndicate. Although they found some forensic evidence at the garage, there were no human remains recovered. The unsolved case remains assigned to the State Police’s major crimes unit and is being treated as a murder investigation.

“The investigation regarding the missing-person case of Michael Ahern is still open and ongoing,” Saratoga County District Attorney Karen Heggen said.

Ahern’s disappearance led to Brady being questioned last year after he and his biker associates were monitored by police for several months. No members of the club have been accused of wrongdoing and no charges have been filed. During their surveillance of the group, investigators also learned a troubling allegation that Brady had purported to carry teeth in his pocket that he boasted belonged to someone who had disrespected their club. The Times Union could not independently verify if that allegation was connected to Ahern’s disappearance.

At least one member of the club also had posted a message on Facebook that appeared to taunt law enforcement investigators: “No body, no crime,” it read, according to a person who viewed the post, which has since been removed.

Within the ranks of the local chapter of East Coast Syndicate, whose members come from across the Capital Region, Brady has been an imposing figure: a one-time amateur mixed martial arts fighter with a 340-pound frame and a reputed willingness to use violence to punish the club’s perceived enemies, or anyone who may disrespect its members. Although the members often post images of their gatherings on social media, Brady is a virtual ghost in that online realm.

His tattoos include Irish Pride along his neckline and FSU across his chest, which indicates his prior ties to another violent motorcycle club based in Troy — Friends Stand United.

In 2006, Lionel Bliss Jr., a Cohoes resident and member of FSU, was sentenced to five years in prison for delivering the fatal blows, including a kick to the head, to a man beaten to death outside a Troy bar where Bliss and other members of his motorcycle club worked as bouncers and hung out.

Unraveling

It’s unclear when Brady might have become affiliated with FSU or left that group to form his East Coast Syndicate chapter. The bylaws of his club were written in November 2014.

Still, there had been signs of trouble in Brady’s life before his arrest last weekend. A year ago, he was arrested in Ohio on charges of drug possession and carrying a concealed weapon. The charges were reduced to misdemeanors as part of a plea bargain.

His wife, a school teacher, in September filed a petition for divorce that remains pending, according to court records. Following his arrest, Brady noted he is “divorced,” and during an interview with law enforcement officials last year had allegedly confided that he was addicted to methamphetamine and frequently hung out with prostitutes, according to a person briefed on the details of that interview.

Brady may also face additional charges in connection with his Oct. 24 arrest: Police said they recovered from his residence drugs and what appeared to be materials used to make explosives.

Make sure you have subscribed to our Facebook page or Twitter to stay tuned!

Source: Times Union