Five years ago today, Patrick Harris and a few friends from his motorcycle club rode from Austin to Waco to take part in a regional meeting to learn about new legislation affecting motorcyclists.

He and his friends had just pulled into the former Twin Peaks restaurant parking lot at about noon that Sunday and had not even gotten off their bikes when the first shots rang out to begin the deadliest single day in American motorcycle groups’ history.

Harris and his friends dove for cover behind parked cars and were among close to 200 bikers arrested and jailed under $1 million bonds after nine bikers were killed and 20 others were injured in the biker battle on May 17, 2015.

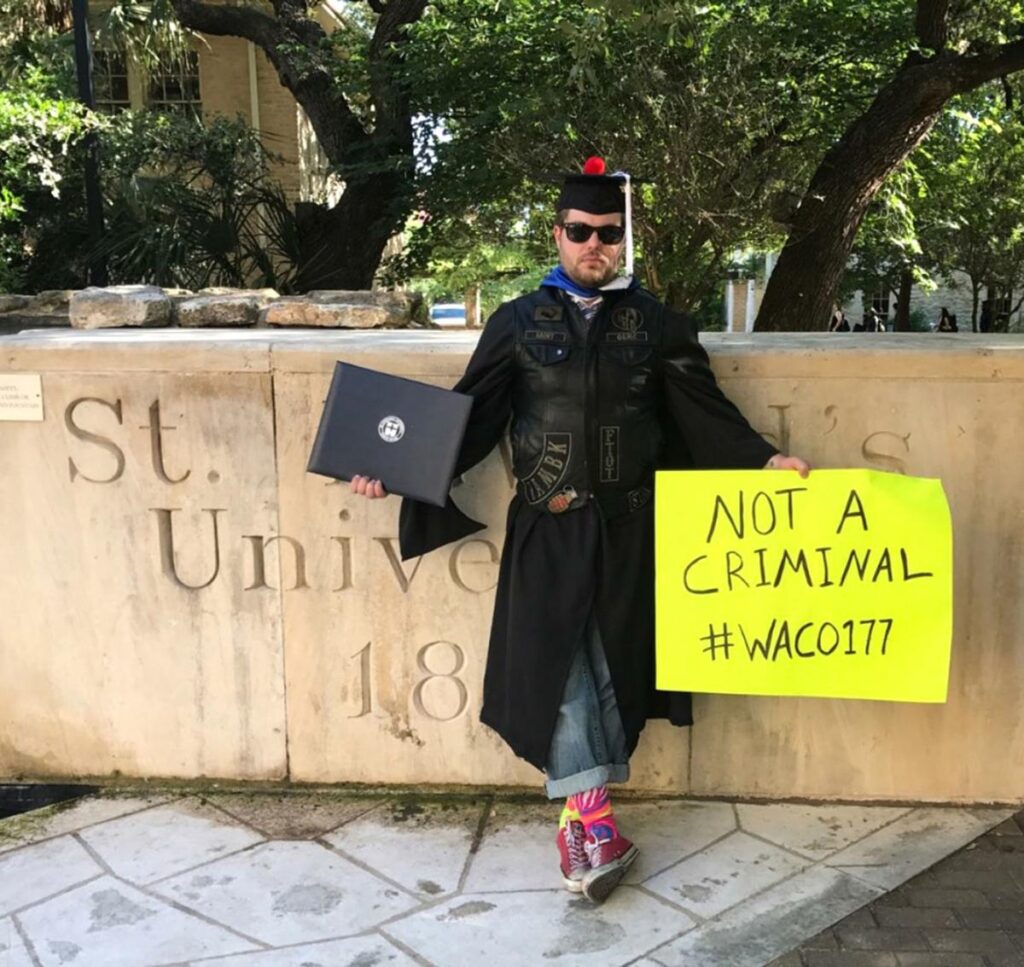

In the years since, the 32-year-old Austin resident has earned a master’s degree in counseling and now is working on his doctorate in mind-body medicine while working as a psychotherapist and teaching undergraduate psychology courses at Huston-Tillotson University in Austin.

But in the aftermath of Twin Peaks, Harris, whose parents, stepfather and uncle are police officers, spent 11 days in the McLennan County Jail. His landlord kicked him out of his apartment. He was rejected for a job with a state health and human services agency, and he was expelled from Mexico while on his way to work with sick children at a clinic run by the celebrated Dr. Patch Adams.

Harris thought he had done a pretty good job of moving beyond the layered ripple effects of his treatment at the hands of the McLennan County justice system when he got a notice to renew his passport a couple of months ago. Mindful that his arrest at Twin Peaks got him red-flagged and kicked out of Mexico, Harris said he decided to check to see if he is listed on the Texas gang database.

Turns out his hunch was correct, a troubling discovery five years after his arrest on charges for which he never was indicted. So Harris decided there was no use to try to renew his passport, at least until his civil rights lawsuit against the city of Waco and various officials is resolved in federal court. He might try to get his record expunged after that, he said.

Until then, he hates that there are limitations on his freedom five years after he claims he was arrested without cause and wrongfully detained for 11 days.

“That is probably the most pressing issue for me right now, not knowing where I can and can’t go,” Harris said. “I know for sure I can’t go to Mexico, but now I don’t even have a passport to go to other countries. That is incredibly frustrating. This whole ordeal kind of made me lose faith in the criminal justice system, knowing that even when you are in the right, when you are innocent, that it doesn’t mean much.

“When you have somebody who has a vendetta against you, you can have it all taken away. Five years later, I still can’t leave the country. I don’t know what pops up on background checks, and profiling of bikers has only gotten worse.”

Harris still rides with the Grim Guardians motorcycle group. He just sold the Kawasaki Vulcan Drifter he was riding at Twin Peaks and got a Harley Davidson Dyna.

“You have this paradox when you attack a disenfranchised group,” Harris said. “I think the government used Waco to try to scare the motorcycle groups from gathering, but it worked the opposite. Where I think law enforcement thought it would make us scatter like roaches under the light, it only brought us together even closer and made us stronger as a community and makes us want to fight the injustices of motorcycle profiling.”

Harris said he grew up with a strong sense of justice that temporarily might have been shaken, but not destroyed.

“The system works. I think when it works, it works. The system is not corrupted. I think people get corrupted and people have biases and strong aspirations, but I don’t think the system is flawed,” he said. “I think bad people should be punished and good people should be rewarded, but the police did that to themselves. It was their fault. With their shoot-first-and-ask-questions-later mentality, if there is any blood on anybody’s hands, it is on theirs.”

A number of bikers arrested at Twin Peaks five years ago declined comment for this story, with many saying they are just trying to move on with their lives. Others did not return phone messages.

More than 100 bikers and their families had planned to gather Saturday at the Palms Lounge in New Braunfels to commemorate the anniversary and to honor the memory of Jesus Delgado Rodriguez.

Known as Mohawk, Rodriguez, who was not affiliated with a biker club, was killed at Twin Peaks. However, his family members canceled the event because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dallas attorney Don Tittle represents more than 100 bikers in civil rights lawsuits that named McLennan County, the city of Waco, former McLennan County District Attorney Abel Reyna, former Waco Police Chief Brent Stroman and other state and local officers as defendants.

In recent rulings, U.S. Judge Alan Albright has thrown out the cases of about 94 of the bikers, so far leaving partially intact the cases of the 35 or so bikers who were not indicted. Albright’s rulings basically state that the grand jury, by issuing 155 indictments in the shootout, constitutes evidence that there was adequate probable cause to arrest all 192 people who went to jail.

“I have noticed there is a reluctance by a lot of people to revisit Twin Peaks because it was such a horrible chapter in their lives and they have gotten past it and don’t want to keep revisiting it. They want to move on,” Tittle said. “Five years after, there has not been a single deposition taken in the civil lawsuits, and the fact that they are essentially stalled pretty much speaks for itself. It is tough to explain to innocent people who were jailed and who lost jobs that five years later not much has happened.”

Reyna, the two-term district attorney, bore the brunt of criticism for directing how the bikers were handled after the shootout. His office helped draft the identical arrest warrant affidavits used to jail the bikers, many for months, before they could arrange to lower the $1 million bonds set by Justice of the Peace Pete Peterson.

Reyna, who lost his reelection bid by 20 percentage points to Barry Johnson, declined comment, saying he would honor his attorney’s request not to discuss the matter because of the pending civil suits.

With some attorneys and their clients clamoring to go to trial to prove their innocence, Reyna hand-picked Jake Carrizal, then Bandidos Dallas chapter president, to stand trial first. His case turned out to be the one and only trial in the entire episode. Reyna dismissed the majority of other cases while leaving his successor and a few special prosecutors appointed in a handful of cases to dismiss the rest.

County officials beefed up security at the courthouse for Carrizal’s trial, which ended in a hung jury and a mistrial that cost the county about $1 million to orchestrate. While Carrizal’s trial revealed that Waco police officers on the perimeter of the restaurant shot and killed four, possibly five, bikers, the results of the criminal prosecutions meant that no one was held criminally responsible for the deaths, injuries and damage caused by the chaotic melee.

Byron Harris, a writer and producer for WFAA.com and an investigative journalist for 44 years, also is finding it difficult to get Twin Peaks defendants to speak to him for a two-part, two-hour documentary he is putting together.

Harris, who has won two Peabody Awards, six duPont Awards and four Edward R. Murrow Awards in his distinguished career, is calling his documentary ”Motorcycle Justice” and is trying to sell it to a major media company such as the HBO or Netflix.

He has conducted a dozen interviews so far and has produced a trailer in his effort to drum up support and interest in the project.

“Twin Peaks was one of the biggest travesties of justice I have encountered as a reporter involving both good and bad people,” Harris said. “There were lots of good guys who were incarcerated and had their lives ruined and bad guys who got off the hook. And from the travesty of justice standpoint, prosecutorial incompetence. Every lawyer I talked to was just astounded at what the prosecutor did, what the judges did and didn’t do and the amount of time it took.”

Dallas attorney Clint Broden represented several bikers whose cases were dismissed and is working with Tittle on a number of the civil cases. He said he still finds it amazing that authorities can “cause that much havoc in people’s lives and not have a price to pay for it and not be held responsible.”

“Looking back, I hope we have learned several things,” Broden said. “I hope we have learned to pay more attention to the people we elect. Second, the media has to question more what they are being fed by the authorities and care more about getting it right than getting it first. The courts and judges have to look more critically about what they are being told by district attorneys. And fourth, just the fact that people are doing business as usual isn’t an excuse to continue doing business as usual.”

Make sure you have subscribed to our Facebook page or Twitter to stay tuned!

Source: Waco Tribune-Herald